Due Sunday, September 4nd

Once you have logged in to you Word Press site, and changed your password, your job is to become comfortable navigating Word Press by working on configuring and personalizing your blog.

When you log in you will have access to your WP dashboard. In the top navigation bar you can click on “My Blog” to go to your site and view the changes you make.

Here is what we would like you to do:

- Change the title and tagline (subtitle): Go to Settings > General. Add your own title and tagline. Think about what you are doing or consult the Century America blogs for examples. Remember, you can change the title or tagline later;

- Add a page or pages: On the dashboard go to Pages > Add New. Pages are one way to organize information on a blog. Create and compose a brief biographical statement (100 words) on an “About” page. Add an image of yourself, if available, by clicking the media icon. We will also use the bio and the image on the main course page as well. Remember, you can add additional pages or change the title of the page or pages later;

- Add a couple of links to your blog: Go to links > add new. Add the COPLAC site: www.coplac.org. Add our Course Site. And consider adding additional links as the course unfolds;

- Add a Widget: Go to Appearance > Widgets. Add “Recent Posts” and save the addition. The widgets you add will appear in the sidebar of the “Twenty Sixteen” theme. Recent Posts will in effect create a table of contents for readers of your blog. Note well the need to create brief and descriptive titles for your blog posts.

The following steps are optional

- Go to appearance > customize and add a header image

- Consider changing the WP Theme: This is optional. But some of you may want to play around with the visual elements and content configuration on your blog. Go to appearance > themes. While there is no need to change your blog theme from the default “Twenty-Sixteen” some of you may want to modify sidebars, where you can add or subtract “widgets” such as “recent posts” or “text” or “categories”). Add background image, if you would like; create a static front page, such as a description or a welcome note; or add a search or tag cloud “widget” to your sidebar.

The more you become comfortable navigating WP at the outset of the course the better off you will be as we use more advanced features of Word Press on your project sites.

In addition, we encourage you browse the Word Press Tutorials. The sixth page of the WP tutorial is about making posts. It will likely be the most useful to you at the beginning of this course. If you would like to add images to your site or to your post, read on to learn how simple this is. The eleventh tutorial, titled “Insider Tips,” is helpful as well. The “kitchen sink” icon in the post/page editor, to take one example, reveals formatting options, enabling you to create headings and indent text, or to use the “paste from word” button that will carry over formatting from a word document.

And don’t worry. If this is all new, as the course gets going, we will talk about the difference between pages (as opposed to posts) and widgets (such as a tag cloud or a list of links that you can use to customize your page and make it easier for a reader to navigate). We will tinker and try and try again as we play with the powerful digital tools. You will come away with a working knowledge of a widely-used and powerful digital platform that will be useful in your college coursework and in your life beyond school.

We will spend some time during our first class meetings responding to any questions, troubleshooting, finding solutions. We will also, of course, be offering support and tutorials on more advanced WP features and the use of WP plugins as the course develops.

For now, the goal is to have fun. Learn by doing what you need to get done.

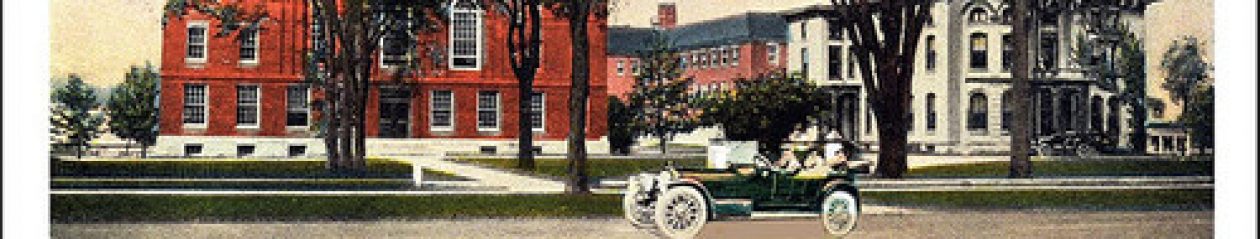

(Mau 6, Bright 6). During this time, the college offered three courses of study: “the two year Elementary English Course, the three year Advanced English Course, and the four year Classical Course.” In addition, students enrolled at the college had to take ”29 semester hours of methodology and 20 of observation and practice teaching” (Mau 8). Notably, from the opening of the school in 1871, the institution reimbursed students for travel expenses accompanying their attendance at Geneseo; however, this practice ended in 1889 due to an increase in enrollment that made the practice financially impractical.

(Mau 6, Bright 6). During this time, the college offered three courses of study: “the two year Elementary English Course, the three year Advanced English Course, and the four year Classical Course.” In addition, students enrolled at the college had to take ”29 semester hours of methodology and 20 of observation and practice teaching” (Mau 8). Notably, from the opening of the school in 1871, the institution reimbursed students for travel expenses accompanying their attendance at Geneseo; however, this practice ended in 1889 due to an increase in enrollment that made the practice financially impractical.