While I initially intended on this post focusing more on national trends in Humanities education in higher ed, the sources I ordered from the library haven’t arrived yet. Luckily, I anticipated this being a problem, so I made sure I had an alternative topic of discussion at the ready. My intended post will be pushed back to next week; this way, I can talk to Mark about his sources for humanities in general education. This week, I’ll continue my discussion of Geneseo’s humanities sequence within the context of the nation’s adjunct crisis. For my project with Emily, I’d like to be able to interview an adjunct professor or two—if possible—regarding their opinions on the organizational structures of the humanities sequence at Geneseo, as well as their opinions on the place of the sequence in the general education requirements of a public liberal arts institution. Using the adjunct crisis as a starting point, I’ll discuss an article that explores humanities and general education at the University of Idaho in order to comment on the state of the humanities sequence at Geneseo. Ultimately, the thinking I’ve done in this post will inform the questions for my interview this week.

“Embedding the Humanities in Cross-Disciplinary General Education Courses” explores humanities education at the University of Idaho. Recently, the university implemented a new strategy for teaching humanities as a general education requirement: contrary to traditional methods of teaching humanities, the University of Idaho has created a plethora of “core discovery” courses which teach the humanities in a way that is oriented towards the exploration of contemporary issues. Rather than exploring time periods or schools of thought, the courses are created topically based on the interests of the professor. The essay listed three main concerns that administrators had with this revised methodology of teaching humanities: the thematic focus, the importance placed on developing intellectual skills such as critical thinking instead of mastering content, and the fact that many of these humanities courses are taught by professors with no experience or training in the humanities. (If I may interject, I think it’s ridiculous that administrators feared that students would “develop intellectual skills” instead of “master content,” and this seems to highlight both the distinctions between empirical/science based disciplines and disciplines of the humanities, as well as the very importance humanities in education).

The authors suggest that the revamped humanities education was a result of students complaining that “’[the humanities] don’t have anything to do with [their] major and [they] just don’t have interest in those subjects” and that “Americans, including Congress, think of the humanities as increasingly marginal contributors to the sum of knowledge and the well-being of society” (279). I find this fascinating for several reasons: for one, this conceptualization of the humanities is entirely different from Geneseo’s statement of purpose regarding the humanities sequence. At Geneseo, the belief is that the humanities sequence provides students with the skills to be a productive citizen. And additionally, comparing the opinions between the two universities evokes the critical juncture between WEB Dubois and Booker T. Washington; University of Idaho’s stance on humanities connotes—though I doubt they conceive of it in these terms—assimilation into the culture of empiricists, while Geneseo advocates for an education that has potential to challenge preexisting structures of knowledge.

In my opinion, however, Geneseo’s humanities, in its current conception—while an important educational experience in its own right—fails to achieve its mission statement as well as it could. And understanding the nation’s adjunct crisis as an means of production that ultimately creates intellectual growth could bridge the gap between the humanities sequence and its intended purpose.

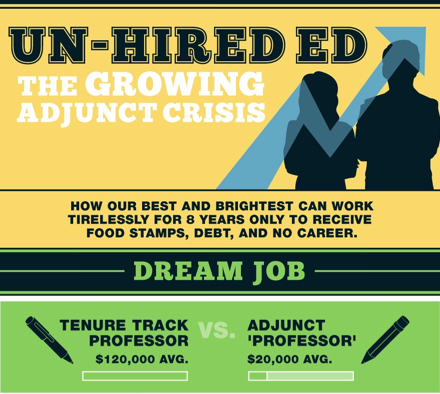

In higher education, institutions often hire adjunct professors to teach introductory courses and high-demand courses, like a university’s freshmen writing requirement and other general education requirements. According to the Atlantic, however, these adjunct professors now make up two-thirds of faculty. While this statistic is not inherently problematic, adjunct professors often receive incredibly low pay, few (if any) benefits, and institutions frequently limit adjuncts’ teaching hours so that the institution is not required to provide health insurance for these “contingent” workers. Ordinarily, adjuncts normally receive about $2,000 for each course they teach—or, in terms of the amount of student tuition that goes towards paying adjuncts, about $65 per student per semester. Additionally, people who wish to make a living as an adjunct professor often need to teach at six different schools in order to put in enough teaching hours for a livable salary.

Research on the effectiveness of adjunct professors as educators (in contrast to tenured professors) is inconclusive; several studies suggest that students learn better from adjuncts, several studies suggest otherwise. But some areas of research on adjunct professorship yield indisputable results: learning is improved when adjuncts are treated better. PhDs who are struggling to gain enough teaching hours to make a livable salary rarely have the time or resources to perform their own research. While this obviously means fewer scholarly contributions that could expand or subvert our understanding of the world, it more subtly implies that students are losing opportunities to perform their own research, or assist in their professor’s research. Additionally, because adjunct professors need to travel to other institutions so frequently, students lose access to the potential resources a professor would otherwise be able to give.

While Geneseo’s humanities sequence—with the goal of providing students with the skills necessary to be productive citizens, and the more broad liberal arts goal of preparing students for the workforce— is taught largely by adjunct professors, the humanities sequence does not teach about the organizational structures of utilizing adjuncts to teach the sequence. In fact, this very line of thinking seems incongruous. However, I believe that if the Geneseo humanities sequence was taught with the aim of analyzing the organizational structures and philosophies undergirding the school’s stance on liberal arts and general education, Geneseo would better prepare students for both the workplace and citizenship. While not all of the schools of Western thought taught in the humanities would work well in an analysis of the course and the status of adjuncts—I’m not sure how Hamlet would fit into this, other than in a discussion of the canon—required readings such as the Communist Manifesto, certain passages of the Bible, and Greek philosophy would certainly work well. In this vein, students would not only learn the content of these texts, but they would learn how to apply these schools of thought in a way that allows for creative re-imaginings of the course they’re currently taking. Accordingly, students would utilize the classroom as both a microcosm for society and the workplace, thus more readily providing students with the ability to function as students, citizens, and workers.

Even though this post wasn’t what I originally planned on researching, I was glad to read the texts I read and take part in this re-imagining of the humanities sequence. Doing so brought many interview questions to mind–questions that I feel get to the heart of liberal arts education (and accordingly, this project): How do we reconcile the ethical ideals emphasized in the teachings of the course with the debatable unethical treatment of those who teach it? How does the current rendition of the humanities sequence achieve the goal of making students better citizens? Would a focus on the organization structures of the course improve any aspect of learning?