From the College Archives

This week I was finally able to visit College Archives, and I found a number of sources that I believe will be very helpful for the website. To start with, I’ve been looking through the undergraduate bulletins (then referred to as “General Catalogs” from 1948-64, encompassing the years in which the G.I. Bill would have had the greatest effect as well as the institution’s transition to a liberal arts college.

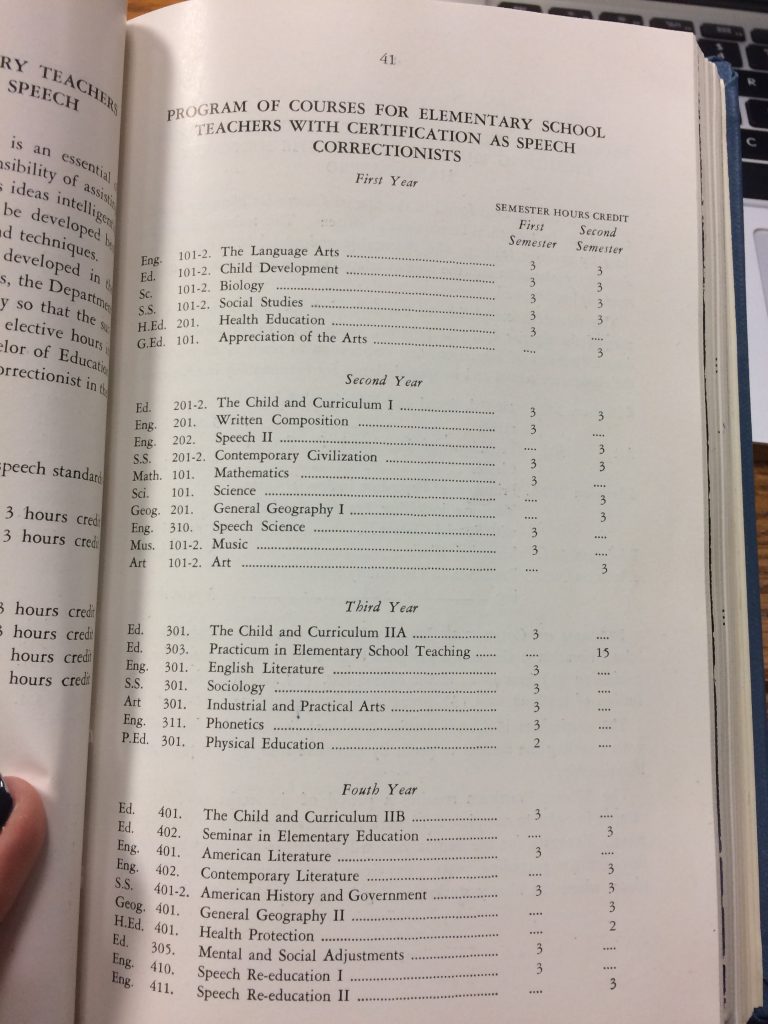

I mostly focused on the number of programs and the general education requirements during the years. The first catalog I examined, from 1948-49, listed only four undergraduate degree programs, all in education (18-19). The college also offered a special program to liberal arts graduates quite similar to our current education programs in a post-war teacher shortage: “Emergency Preparation of Liberal Arts Graduates.–In order to augment the supply of available elementary school teachers and to certify good quality teachers, liberal arts college graduates whose personal characteristics are wholly satisfactory may qualify for elementary school teaching by engaging in an appropriate summer educational program” (24).

While no specifics of general education are mentioned, the requirements for each program contain courses that we

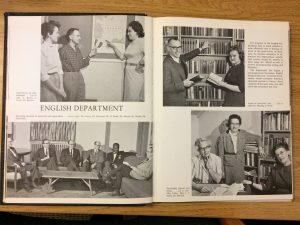

From the 1948-49 catalog

would consider as such, including Biology and “Appreciation in the Arts” (39). These courses are quite similar in each of the four programs, with minor variations.

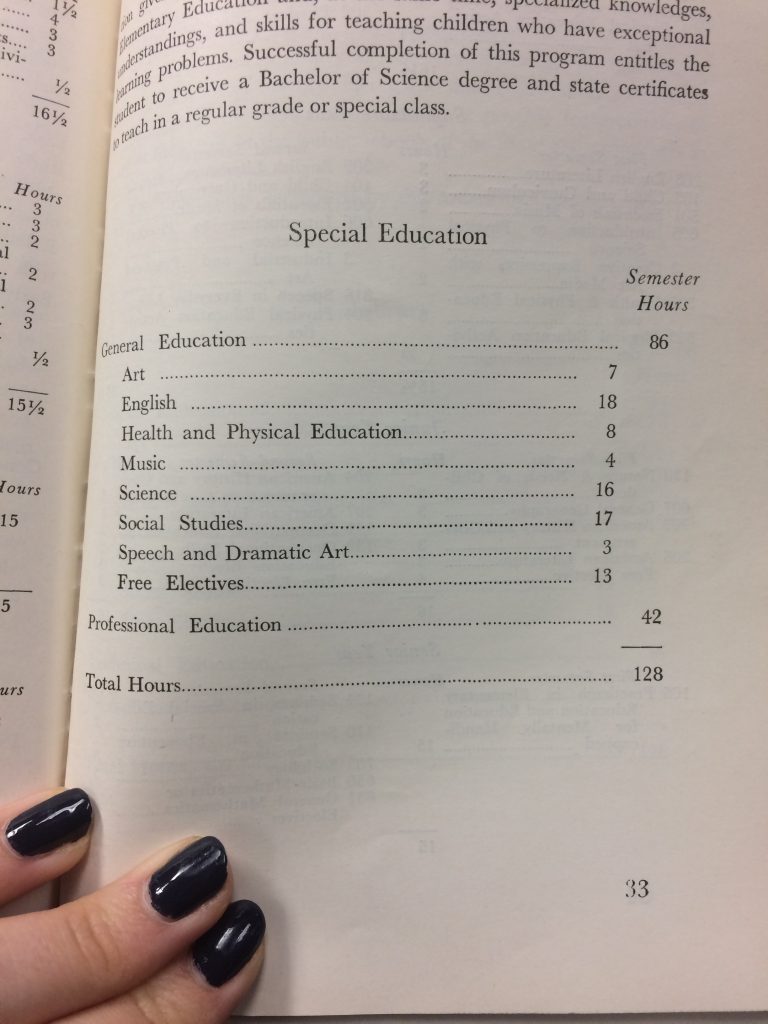

The next catalog, from the academic year of 1950-51, was the first to mention SUNY, established in 1948. The statement about SUNY included a mention that the “State University [was] exploring … the broadening of the curriculum of the teacher colleges,” perhaps hinting at the 1951 directive for all state teachers colleges, including Geneseo, to transition to liberal arts schools within the coming decade (18). In a supplement dated October 1951 (a complete catalog was not produced in ’51-’52), there was a mention of college requirements : “education- 18 hours, English- 14 hrs; social studies- 14 hrs; art- 7 hrs; science- 3 hrs; music- 2 hrs; and health and physical education- 8 hrs” (8-not officially numbered). Until the liberal arts curriculum is implemented in the fall of 1962, these requirements remain generally the same, with slight variations, but they seem to be program requirements rather than college-wide requirements because of how they are listed. They are first listed as “General Education” in the ’55-’56 catalog.

The catalog from 1952-53 includes several hints at the coming transition to the liberal arts. A required minor in liberal arts subject was added to all programs except for library education, but I could find no mention of this requirement in any of the other catalogs prior to ’62, so I’m not sure if this was only required for this one year (17). A statement of support for the liberal arts was also added to the “College Program of Instruction” section: “Students will find that, although this is a professional school, the area of liberal or general education receives great emphasis. A good liberal arts education is a necessary basis of effective teaching” (29). This was also the first catalog in which the areas of study were listed as departments (English and Foreign Language Department, Education Department, etc) (36-55).

The 1962-63 catalog unsurprisingly contained the most widespread changes to the curriculum, as this was the first year the liberal arts curriculum was implemented. Noting the change as part of SUNY’s “master plan,” the purpose statement declared that “the College [became] a multi-purpose institution with broadened curriculums in the liberal arts and sciences along with a strengthened program of professional preparation for the teaching of secondary English, social studies, mathematics, and the sciences” (22). A college-wide Common Core was put in place, and many of the programs are similar to what we have today, including elementary education programs with a required liberal arts concentration and secondary education programs with subject certification (today, the degree is awarded in the liberal arts discipline with teaching certification) (60-67). I’m planning to look through the undergrad bulletins through the addition of the Humanities sequence, in the mid-’70s.

I’ve been approaching these catalogs as something of an unbiased baseline in terms of the curriculum, and while this may be true to a point, they were also primarily created as a resource for students. I’m also planning to look through Faculty Senate records as well as archives of the Lamron, the student newspaper, from the same time period to create a more compelling narrative for the website.