Our class discussion today about the “sympathetic researchers” in Buurma’s article made me think about the Humanities sequence at Geneseo, considered to be (and advertised as) the cornerstone of our liberal arts curriculum. The sequence consists of two courses that examine the development of western civilization primarily through “Great Books,” and are primarily taught by English, history, and philosophy professors (more in-depth description here). Most relevant to our discussion is the fact that all students are required to take these classes as a graduation requirement, and students of all majors and backgrounds end up in the same classes. This mixture of students often produces the variety of insights that Mark mentioned when discussing interdisciplinary classes. I’m currently taking Humanities II, and the range of opinions in what is still mostly an English class (I will admit I’ve purposefully taken both courses with English professors) is refreshing compared to my major classes, where everyone is trained to look at the texts in the same ways (not that this leads to everyone having the exact same thoughts).

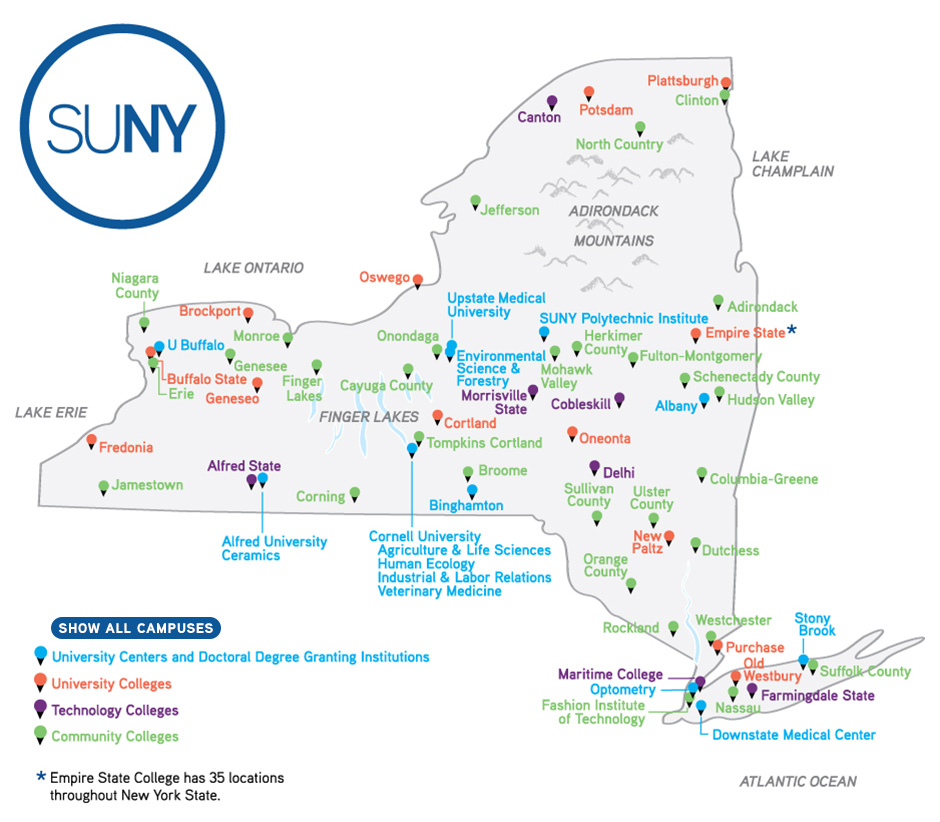

In terms of my site, I’m still not exactly sure how Humanities will figure in. I discovered through some (very brief) googling that at least among the SUNY schools, our program is quite unique; several schools have humanities general education requirements, but a number of different courses that fulfill them (including Albany, Binghamton, and Purchase).

Furthermore, the history of the program at Geneseo is more than a little contentious. As I learned when researching for my first blog post about the college’s history, the program took several years to fully establish after its conception. From what I can tell, the curriculum has not drastically changed, but I hope to find further information on this in the archives (which I plan to visit within the next couple weeks). On the first of class this semester, my Humanities professor told the class that since its establishment, various forces have been trying to remove the sequence from the graduation requirements. While I currently don’t have much to back this up, I think it’s entirely believable, because most current students dread taking the courses (I will attribute this partially to traumatic registration experiences).

In my interviews with current students and alumni who took the courses, I definitely intend to address this aversion to Humanities; the requirement certainly isn’t kept a secret during the admissions process, so why choose a school like Geneseo if you know you will hate these classes? I also want to discuss this with the professors who teach the courses. While I’ve gone back and forth on the possibility of interviewing a greater ratio of English professors than those in other departments, I currently feel that interviews with a number of different professors who teach/have taught these courses may be more beneficial to the project as a whole than a more equal spread across the disciplines.

My research has been at somewhat of a standstill this week as I’ve had a number of papers and midterms, but, as I mentioned earlier, I’m hoping to visit the College Archives after my break this weekend. Over the weekend, I’m going to try looking more closely at some of the specifics of the site design—this may be more easily and efficiently done once I’m farther along in my research, but becoming more familiar with WordPress and the like can’t hurt.